Crystal Hana Kim on the in-between phases of aging and storytelling across generationsInterview by Harriet KimFrom the beginning of this volume's journey, we wanted to explore the experiences of aging in relation to the people and world around us (no small feat), which is why Crystal Hana Kim's work struck a chord with us. If you’ve come across any of her writing, you will know that Crystal has a distinct voice, one that is flowing and expansive while speaking directly to the heart of the matter. We wanted to know what she thought about the topic of aging in place so we spoke with her about the transitions and in-between phases that come with aging, a reverence for the mountains, and storytelling and lessons across generations.

This interview was edited for grammar, flow, and clarity.

It means readying myself for the new-ish experience of mothering an infant (again) and putting a book out into the world (again). I want to be constantly growing in my thinking, in my empathy, in my writing, and in my relationships. At the same time, there’s a lot of routine in my life, which requires a different sort of patience and attention.

HK: Congratulations on your growing family and upcoming novel! There is a kind of tenderness in the way you write about this in-between stage that is beautiful.

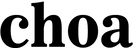

CHK: What a beautiful question. I’ve been interested in the ground beneath us and the plants that surround us since I was young. I grew up in a household with two religions: Catholicism and a reverence for nature. While my mother took my sister and me to church frequently, my father often took us hiking on Sundays. He has a devotion to the mountains that always interested me.

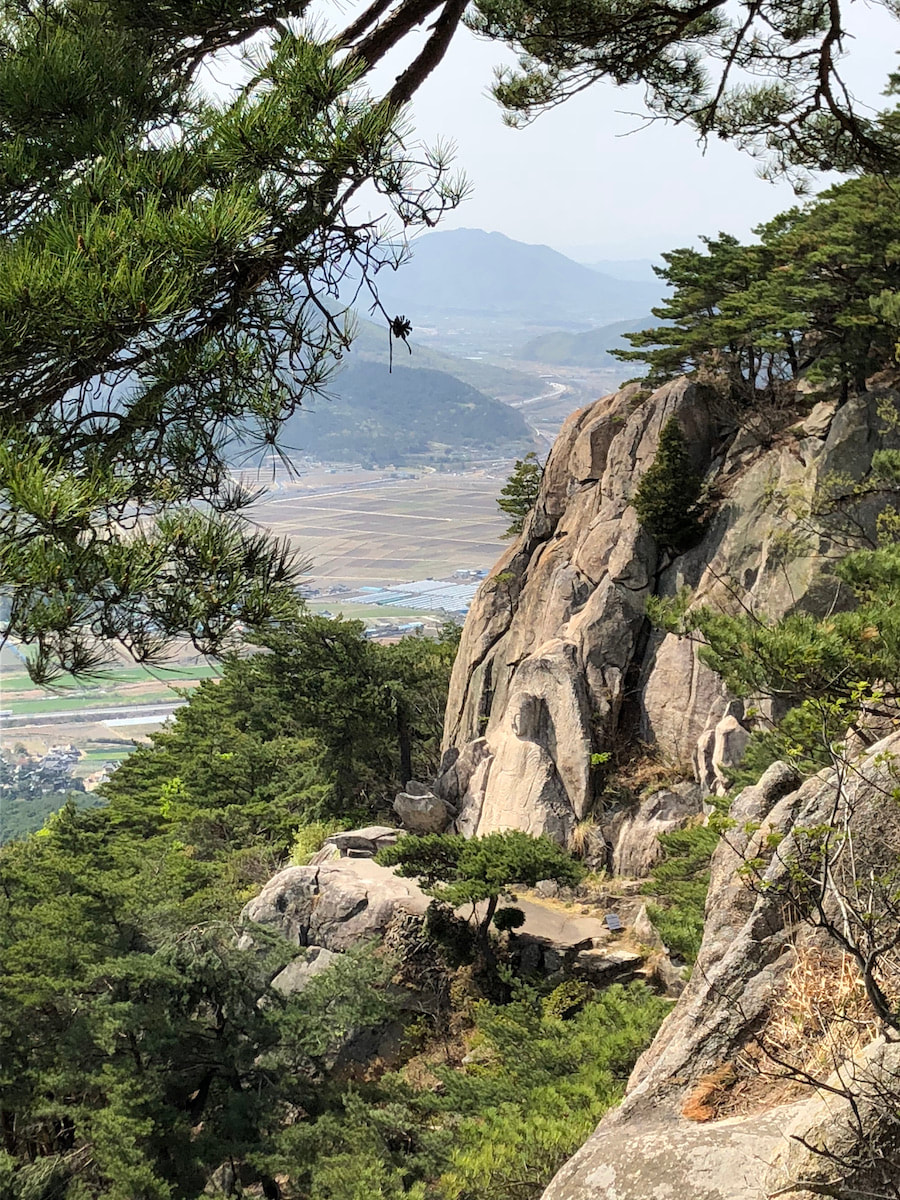

When writing If You Leave Me, it was important to me to research the indigenous plants of Korea, to populate important scenes with these flowers. I wanted the natural history of our country, which has been ravaged by colonialism, war, and foreign powers, to speak to our power. The cover of the book reflects the importance of the land—the native flowers all represent an integral character or scene in the novel. When I think of Korea, the first sensory detail that comes back to me is the smell—of the air, of the greenery—and then the mountains that can be seen in the distance, wherever you are. HK: Especially during the last couple of times I visited Korea, there was a part of me that just couldn’t get over how “unphased” people in a city like Seoul seemed living among the mountains, but it’s just so integrated into their lives. Perhaps it’s a big generalization, but it feels like as diasporic people, there is a kind of devotion to the mountains that I’m not sure ever leaves our bones, and I appreciate that you trace that history as a kind of sensory experience in your novel.

And it seems like such a profound way to bear witness to your grandmother, in the ways that you talk about her and her stories, especially in reference to If You Leave Me. Can you tell us a bit more about your grandmother’s storytelling? Is your own form of storytelling influenced by it? CHK: When I was born and my parents were forging a life for themselves in the United States, my maternal halmuni came to take care of me. She didn’t know English, yet she uprooted her life for a few years. I’ve been so grateful ever since. Also, my mother is the only one of her children to live outside of Korea, so the time my halmuni and I spend together feels precious. Perhaps because these temporal and geographic distances allow for more openness, my halmuni has spoken to me honestly about her life. She loves to tell stories of her youth—often laced with grief—about fleeing her home during the Korean War, of having to marry for security, of the regret of not receiving a full education. Those stories changed my understanding of not only my family, but of my country and heritage. When I began writing seriously, I knew that the grief she experienced would be the starting point of a novel, which I then, of course, fictionalized to include all my other curiosities and preoccupations. HK: Your second novel is a different kind of story, but also one that is about “grief, violence and oppression, resilience, and how to reckon with a shared history,” to quote your Instagram post about it. Are there certain curiosities preoccupying your mind now, either as you write this novel or as you move through this current in-between stage generally? CHK: My second novel, The Stone Home, which will be published in 2024, is set in what was known as a “reformatory” institution in South Korea in 1980. In fact, these “reformatories” were state-sanctioned vehicles for oppression. This second book is tied to my first through the preoccupations that filled my mind while writing—oppression, violence, how to reckon with our history, as you mentioned—but it also pushes a path forward because I was newly interested in community and how we come together in moments of hardship to survive. I believe my preoccupations will change as I age and as I ask new questions about the world around us. Right now, I’m in a stage of receiving, filling the well, so to speak. I’m reading and trying to remain open so that I can ask new questions in my third book. I’ve been drawn to stories about Asian American—and particularly Korean American—identity lately. Perhaps my third book will be set in the United States. I don’t know yet, but I’m open to all ideas.

I recently read a debut novel coming in early 2023 called Sea Change by Gina Chung, which I loved for its portrayal of a young Korean American woman dealing with heartache while caring for an octopus (yes, an octopus!) at her local mall aquarium. I’m also looking forward to reading Ryan Lee Wong’s Which Side Are You On.

HK: Thinking about these stories (and lessons) from colleagues, as well as those from your parents and halmuni, it seems they have shown up for and moved with you in different ways and during different times of your life. As a parent and a teacher, are there stories and lessons you've learned from your children and students?

CHK: The inquisitiveness I see in my child reminds me to be curious. As adults, it’s easy for our days to fall into patterns, ruts. Sometimes, it’s harder for us to be vulnerable and try new experiences. My child’s excitement reminds me that aging does not mean I can’t seek to learn too. Why not try a new hobby, or pick up the flute again, or play a new sport? My son encourages me to try. My undergraduate and graduate students teach me similarly, though in the scope of writing. They are so adventurous on the page, and they expand my understanding of the capabilities of writing and art-marking. Crystal Hana Kim is the author of If You Leave Me, which was a Booklist Editor’s Choice title and named a best book of 2018 by over a dozen publications. A 2022 recipient of the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 Award, a 2022 Creative Capital Award Finalist, a 2021 Jerome Hill Artist Finalist, and a 2017 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize winner, she is currently the Visiting Assistant Professor at Queens College and a contributing editor at Apogee Journal. Her second novel, The Stone Home, is forthcoming from William Morrow / HarperCollins in 2024. | Web: crystalhanakim.com

|